The Q+A

Which conceptual framework did you use for your research and why?

How does your specific identity and life experience impact the research?

What are the values and principles behind your research?

Which specific ethical considerations are central to your research?

How does your project apply Indigenous theory?

Why is your presentation like this? What are we doing here exactly?

Where did the idea for this project come from?

What were your research questions?

What were you hoping to discover?

What research methods did you use or consider using? Which ones were most useful?

What’s unique about the site? What opportunities and constraints are present?

Gathering Knowledge

What/who is Everyone Village (EV)?

How have you been involved at EV?

What’s the history of the EV site?

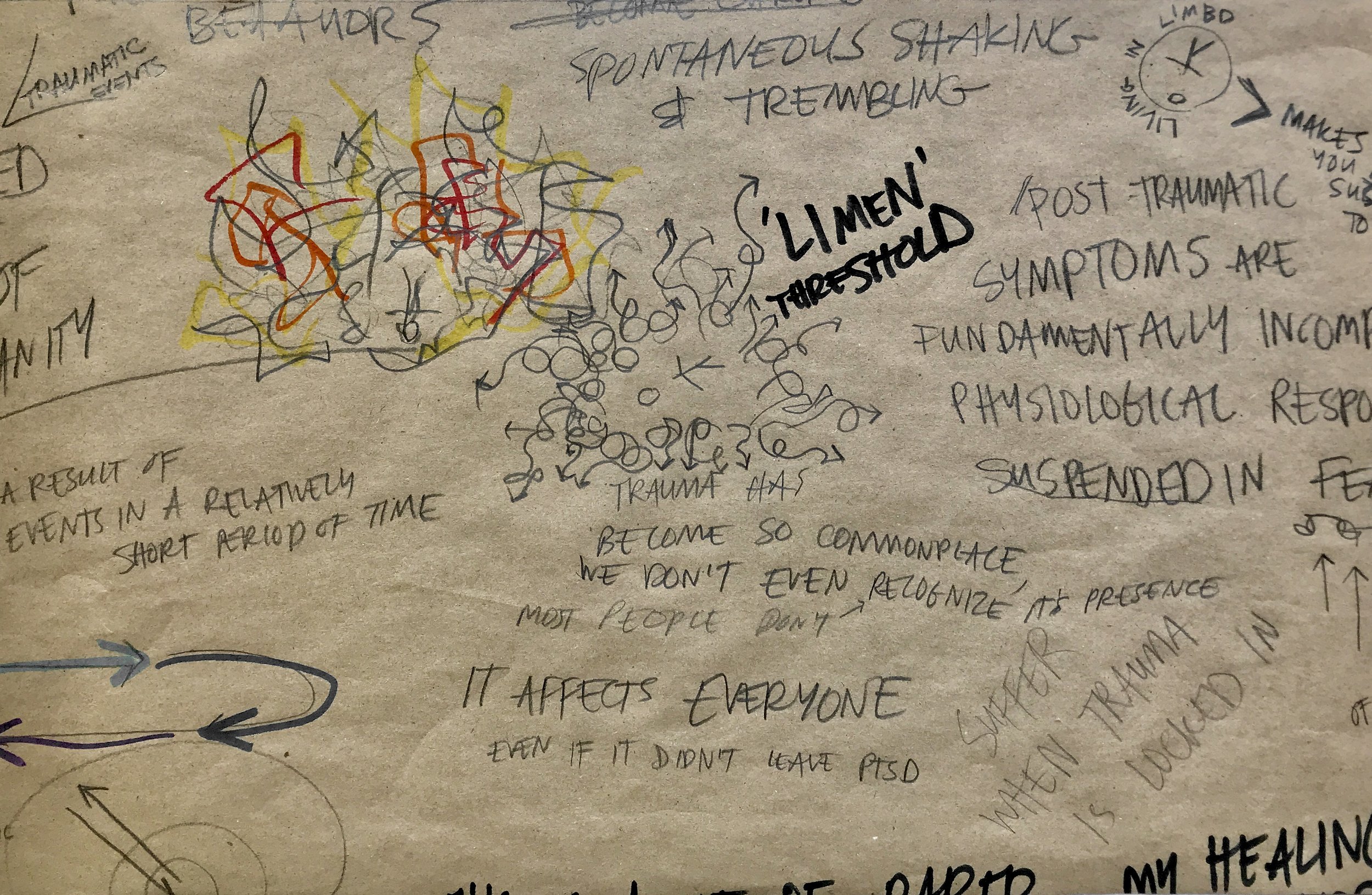

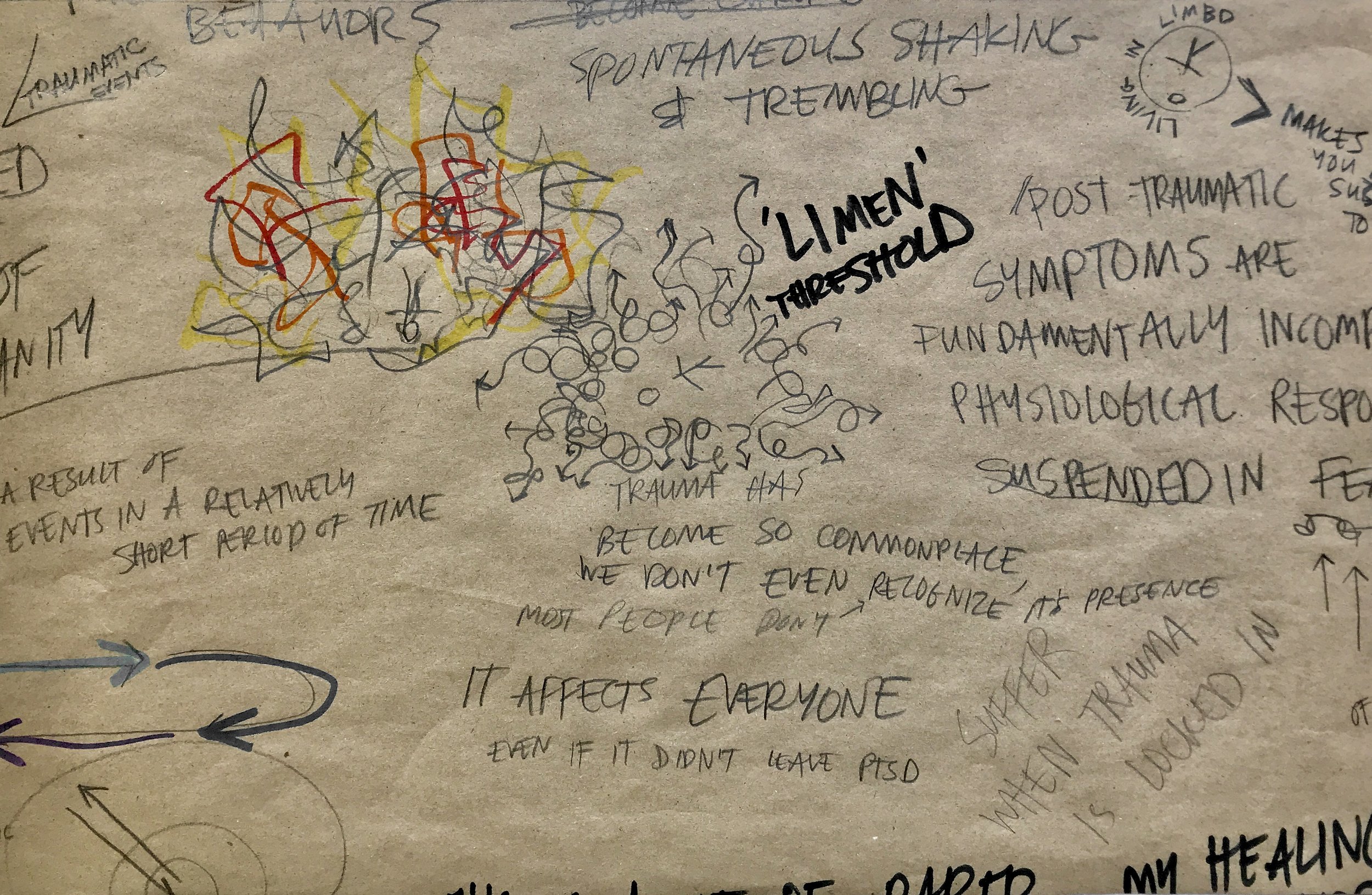

What is trauma?

What does it mean to be “trauma-informed”?

Why is it important to talk about trauma in relation to homelessness and transitional housing?

What is “trauma-informed design”? Could you explain your framework?

How can trauma-informed design be applied in landscape architecture? And in the context of transitional housing?

What are your design goals and objectives given the site and circumstances?

What are your design principles?

Giving Back

Despite being process focused, what type of end products did you end up with as part of your project at Everyone Village? What were your design outcomes? What were your process outcomes?

What did gaining consent look like in your process?

What do you feel like you were able to give back as a result of your project?

How would you like to facilitate the process in the future to make greater space for giving back?

Who played a large role in this project that you’d like to recognize?

Researcher Preparation

What were your academic and personal motivations for the research?

Whom do you consider key stakeholders in this project? Who were some of the co-researchers on this project?

Who and what were some big outside influences on your work?

Could you tell me a little more about yourself?

What’s your educational and professional background?

Where do you call home?

Who do you call family?

What are some of your core values?

Why did you decide to come back to school for landscape architecture?

Who’s a good boy?

Research Preparation

Meaning Making

How were your design goals, objectives, and principles expressed through your designs? Which components are trauma-informed?

What did you discover? What are your big takeaways from this process?

Did anything surprise you?

What would you have done differently?

What did you learn about yourself from this process?

How has your process changed over time?

Mood tracker of the first month of grad school

3

What are the values and principles behind your research?

4

Which specific ethical considerations are central to your research?

5

How does your project apply Indigenous theory?

6

Why is your presentation like this? What are we doing here exactly?

1

What were your academic and personal motivations for the research?

2

Whom do you consider key stakeholders in this project? Who were some of the co-researchers on this project?

3

Who and what were some big outside influences on your work?

4

Could you tell me a little more about yourself?

5

What’s your educational and professional background?

6

What are some of your core values?

7

Where do you call home?

8

Who do you call family?

9

Why did you decide to come back to school for landscape architecture?

10

Who’s a good boy?

1

What inspired the idea for this project? Why focus on trauma-informed design?

2

What were your research questions?

3

What were you hoping to discover?

4

Which research methods did you use? Which ones were the most useful?

5

What’s unique about the site? What are the opportunities and constraints?

1

What is Everyone Village (EV)? Who is EV?

2

How have you been involved at EV?

3

What’s the history of the EV site?

4

What is trauma?

5

What does it mean to be “trauma-informed”?

6

Why is it important to talk about trauma in relation to homelessness and transitional housing?

7

What is “trauma-informed design”? Could you explain your framework?

8

How can trauma-informed design be applied in landscape architecture? And in the context of transitional housing?

9

What are your design goals and objectives given the site and circumstances?

10

What are your design principles?

1

How are your design goals, objectives, and principles expressed through your designs?

2

What are your big takeaways?

3

Did anything surprise you?

4

What would you have done differently?

5

What did you learn about yourself from this process?

6

How has your process changed over time?

1

Despite being process focused, what type of end products did you end up with as part of your project at Everyone Village? What were your design outcomes? What were your process outcomes?

2

What did gaining consent look like in your process?

3

What do you feel like you were able to give back as a result of your project?

4

How would you like to facilitate the process in the future to make greater space for giving back?

4

Who played a large role in this project that you’d like to recognize?

Would you walk me through your process a little bit more?

This project started as an opportunity for me to learn more about trauma and the impacts of trauma on my ability to perform in school. I happened to hear about trauma-informed design through one of the founders of Everyone Village. She was curious to incorporate it since we were working with a population that often has co-occurring traumas. It felt like an opportunity for me to explore and learn about trauma for myself but also, perhaps to apply that learning in a context where it might be useful to my community.

I started working as a lab assistant for Landscape for Humanity with Professor Yekang Ko in her “Design for Climate Action” course. I was co-facilitating a group of undergrad students with Sarah Loquist, a Ph.D. student in landscape architecture. It provided a great introduction to the Everyone Village community.

The next term, I took Jennifer O'Neill's “Indigenous Research Methods” course. I found overlaps in values between the indigenous research process and the goals and values of the staff at Everyone Village. They both focused on a relational model, centering the relationships in the process of learning and working, and the practice of trauma-informed design was right in line with that.

And at the same time, one of the co-founders got us connected with a grant to learn from a transitional employment program in California called The Homeless Garden Project, which used organic farming training as a way to support people experiencing houselessness.

From there, it just kind of blossomed into this opportunity to understand how landscape and the trauma-informed design process could help strengthen the relationships at Everyone Village. The transitional employment component at a transitional housing community was an opportunity to kind of reinforce the trauma-informed design component of empowerment and community. There was a lot of layering and serendipitous overlapping of things.

And recently, we applied for a grant to build out this landscape-based transitional employment program and the family foundation believed in our vision so much so that they full-funded the first year.

What is an “Indigenous Conceptual Framework” and why did you choose it for your project?

What is an indigenous research paradigm and why did you choose it for your project with Everyone Village?

This project started as an opportunity for me to learn more about trauma and the impacts of trauma on my ability to perform in school. I happened to hear about trauma-informed design through one of the founders of Everyone Village. She was curious to incorporate it since we were working with a population that often has co-occurring traumas. It felt like an opportunity for me to explore and learn about trauma for myself but also, perhaps to apply that learning in a context where it might be useful to my community.

I started working as a lab assistant for Landscape for Humanity with Professor Yekang Ko in her “Design for Climate Action” course. I was co-facilitating a group of undergrad students with Sarah Loquist, a Ph.D. student in landscape architecture. It provided a great introduction to the Everyone Village community.

The next term, I took Jennifer O'Neill's “Indigenous Research Methods” course. I found overlaps in values between the indigenous research process and the goals and values of the staff at Everyone Village. They both focused on a relational model, centering the relationships in the process of learning and working, and the practice of trauma-informed design was right in line with that.

And at the same time, one of the co-founders got us connected with a grant to learn from a transitional employment program in California called The Homeless Garden Project, which used organic farming training as a way to support people experiencing houselessness.

From there, it just kind of blossomed into this opportunity to understand how landscape and the trauma-informed design process could help strengthen the relationships at Everyone Village. The transitional employment component at a transitional housing community was an opportunity to kind of reinforce the trauma-informed design component of empowerment and community. There was a lot of layering and serendipitous overlapping of things.

And recently, we applied for a grant to build out this landscape-based transitional employment program and the family foundation believed in our vision so much so that they full-funded the first year.

-

The fundamental values of this design process are holism and relationality. Rather than looking to generate specific and precise knowledge—an approach common through a Western paradigm—this research process aims to understand the interconnected factors and relationships that influence a person’s capacity to find stability and security in their lives—particularly after experiencing houselessness.

This was specifically important to me in this process because of the complex nature of homelessness and trauma. The National Alliance to End Homelessness writes, “To end homelessness, a community-wide coordinated approach delivering services, housing, and programs is needed.”

In the article Two Steps Forward: Promoting Inclusive Infill Development with Middle Housing by Right and Increased Protections for Tenants, author Sarah J. Adams Schoen writes,

“Over the last few decades, the national median rent has risen twenty percent faster than inflation and the median home price has risen forty-one percent faster than inflation. At the same time, "real median income of households in the bottom quartile increased only 3 percent between 1988 and 2016, while the median income among young adults in the key 25-34-year-old age group was up just 5 percent.”” (Schoen, 2019).

-

The fundamental values of this design process are holism and relationality. Rather than looking to generate specific and precise knowledge—an approach common through a Western paradigm—this research process aims to understand the interconnected factors and relationships that influence a person’s capacity to find stability and security in their lives—particularly after experiencing houselessness.

This was specifically important to me in this process because of the complex nature of homelessness and trauma. The National Alliance to End Homelessness writes, “To end homelessness, a community-wide coordinated approach delivering services, housing, and programs is needed.”

In the article Two Steps Forward: Promoting Inclusive Infill Development with Middle Housing by Right and Increased Protections for Tenants, author Sarah J. Adams Schoen writes,

“Over the last few decades, the national median rent has risen twenty percent faster than inflation and the median home price has risen forty-one percent faster than inflation. At the same time, "real median income of households in the bottom quartile increased only 3 percent between 1988 and 2016, while the median income among young adults in the key 25-34-year-old age group was up just 5 percent.”” (Schoen, 2019).

-

The fundamental values of this design process are holism and relationality. Rather than looking to generate specific and precise knowledge—an approach common through a Western paradigm—this research process aims to understand the interconnected factors and relationships that influence a person’s capacity to find stability and security in their lives—particularly after experiencing houselessness.

This was specifically important to me in this process because of the complex nature of homelessness and trauma. The National Alliance to End Homelessness writes, “To end homelessness, a community-wide coordinated approach delivering services, housing, and programs is needed.”

In the article Two Steps Forward: Promoting Inclusive Infill Development with Middle Housing by Right and Increased Protections for Tenants, author Sarah J. Adams Schoen writes,

“Over the last few decades, the national median rent has risen twenty percent faster than inflation and the median home price has risen forty-one percent faster than inflation. At the same time, "real median income of households in the bottom quartile increased only 3 percent between 1988 and 2016, while the median income among young adults in the key 25-34-year-old age group was up just 5 percent.”” (Schoen, 2019).

-

The fundamental values of this design process are holism and relationality. Rather than looking to generate specific and precise knowledge—an approach common through a Western paradigm—this research process aims to understand the interconnected factors and relationships that influence a person’s capacity to find stability and security in their lives—particularly after experiencing houselessness.

This was specifically important to me in this process because of the complex nature of homelessness and trauma. The National Alliance to End Homelessness writes, “To end homelessness, a community-wide coordinated approach delivering services, housing, and programs is needed.”

In the article Two Steps Forward: Promoting Inclusive Infill Development with Middle Housing by Right and Increased Protections for Tenants, author Sarah J. Adams Schoen writes,

“Over the last few decades, the national median rent has risen twenty percent faster than inflation and the median home price has risen forty-one percent faster than inflation. At the same time, "real median income of households in the bottom quartile increased only 3 percent between 1988 and 2016, while the median income among young adults in the key 25-34-year-old age group was up just 5 percent.”” (Schoen, 2019).

-

The fundamental values of this design process are holism and relationality. Rather than looking to generate specific and precise knowledge—an approach common through a Western paradigm—this research process aims to understand the interconnected factors and relationships that influence a person’s capacity to find stability and security in their lives—particularly after experiencing houselessness.

This was specifically important to me in this process because of the complex nature of homelessness and trauma. The National Alliance to End Homelessness writes, “To end homelessness, a community-wide coordinated approach delivering services, housing, and programs is needed.”

In the article Two Steps Forward: Promoting Inclusive Infill Development with Middle Housing by Right and Increased Protections for Tenants, author Sarah J. Adams Schoen writes,

“Over the last few decades, the national median rent has risen twenty percent faster than inflation and the median home price has risen forty-one percent faster than inflation. At the same time, "real median income of households in the bottom quartile increased only 3 percent between 1988 and 2016, while the median income among young adults in the key 25-34-year-old age group was up just 5 percent.”” (Schoen, 2019).

-

The fundamental values of this design process are holism and relationality. Rather than looking to generate specific and precise knowledge—an approach common through a Western paradigm—this research process aims to understand the interconnected factors and relationships that influence a person’s capacity to find stability and security in their lives—particularly after experiencing houselessness.

This was specifically important to me in this process because of the complex nature of homelessness and trauma. The National Alliance to End Homelessness writes, “To end homelessness, a community-wide coordinated approach delivering services, housing, and programs is needed.”

In the article Two Steps Forward: Promoting Inclusive Infill Development with Middle Housing by Right and Increased Protections for Tenants, author Sarah J. Adams Schoen writes,

“Over the last few decades, the national median rent has risen twenty percent faster than inflation and the median home price has risen forty-one percent faster than inflation. At the same time, "real median income of households in the bottom quartile increased only 3 percent between 1988 and 2016, while the median income among young adults in the key 25-34-year-old age group was up just 5 percent.”” (Schoen, 2019).